Join the UruguayNow mailing list:

UruguayNow in the press

UruguayNow's mix of travel and tourist information on Uruguay, hotel reviews for Montevideo and Punta del Este (coming soon for Colonia), restaurant reviews and tips on excursions, sightseeing and lifestyle in Uruguay has been featured in El Pais, La Republica, MercoPress and on Uruguay's Channel 5 TV and other news media in the country. Internationally, we have had kind mentions in the New York Times and the Daily Telegraph.

Best of the Web

Not yet made it to Uruguay? When you're done with UruguayNow, our choice of the top 6 internet resources for the country is just a mouse click away. In no particular order, they are:

Southern Cone Travel: http://southernconeguidebooks.blogspot.com/

Mercopress: http://en.mercopress.com/

Ola Uruguay: www.olauruguay.com

Retired in Uruguay: http://wallyinuruguay.blogspot.com/

Uruguay Natural: www.uruguaynatural.com

Global Property Guide: http://www.globalpropertyguide.com/Latin-America/Uruguay

For reviews of these sites, please click here.

Other recommended sites

The Uruguayan Invasion

Montevideo meets Merseyside, musically speaking

As with football, Uruguayan music has a rich, influential history that started off with international success that belied the comparatively small size of the country. As all tango aficionados know, Carlos Gardel – the most prominent figure in the history of the genre – was born in Tacuarembó in northern Uruguay (although the emergence of a French birth certificate since his death has added doubt to this). Gardel, however, is not Uruguay's greatest musical claim to fame.

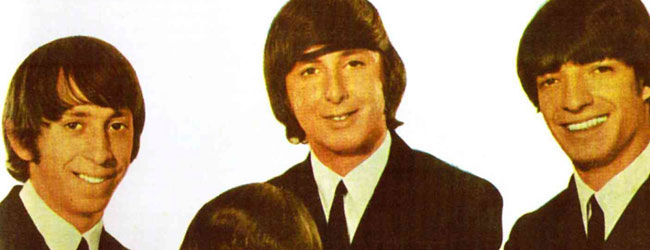

In the middle of the 1960s, spurred on by the music of The Beatles that had by that time spread worldwide, a number of bands formed in Montevideo with the goal of emulating their Scouse idols. Foremost among these was Los Shakers, helmed by Hugo and Osvaldo Fattoruso. With precisely-trimmed haircuts, black designer suits and an assortment of catchy pop originals and covers they began playing in the clubs of Montevideo and Punta del Este. In 1965, after only two years together, Odeon – a Buenos Aires record label then desperate for a big hit – asked them to come over to Argentina to record. It took the band a couple of singles to get into their stride but eventually they produced Rompan Todo ("Break It All"), a song that would become a classic of what became the “beat” movement.

The band's popularity led to other Uruguayan groups getting their chance in Argentina, among them Los Bulldogs, Los Mockers and Los Malditos, all of whom achieved some level of success. After this, Argentine record labels would sign unknown bands simply because they were from Uruguay, similar to the way Liverpool bands were signed up during the Merseybeat craze in England. The Uruguayan Invasion had officially arrived in Argentina.

As with many fads in the Sixties things wouldn't last for the Uruguayan bands. The release of La Balsa in July 1967 by Argentine outfit Los Gatos signalled the end. Here was a successful single written in Spanish – most “beat” songs up to this point were sung in English – and with a harder sound. La Balsa marked the beginning of a specifically Argentine rock. The craze for Uruguayan "beat" bands fizzled out as quickly as it had begun. But it did not mean the end of Uruguay's influence in the music world: this would only come about when the military dictatorship took over in 1973.

One Uruguayan band who did not travel to Argentina was El Kinto. Instead they remained in Uruguay, creating a style of music which would become know as “candombe beat.” They came to prominence in the late 1960s by mixing rock songs with the rhythms of candombe, a Uruguayan style of drumming with strong African roots (read more about candombe here), and chords of bossa nova. It was a completely different sound to the “beat” groups, essentially because its influences were closer to home, and there was a clear willingness to experiment. The band's recordings in 1968 and 1969 (which wouldn't be released until 1977) were – as far as any reliable source notes – the first time that a Uruguayan rock band had recorded in Spanish. Despite limited success as El Kinto, its members would go on to have considerable notoriety: Eduardo Mateo became a musical idol who would serve the last years of his short life penniless; Ruben Rada would form a seminal band T�tem before playing with musicians in Brazil, the USA and Mexico; and the rest would form Limonada, a great “candombe beat” group that would release a single eponymously-titled album of what would now be called “power-pop”.

Meanwhile, the Fattoruso brothers of Los Shakers would achieve the most notoriety of all. They had already shown that they were slightly above the standard of the other “beat” bands with their final Los Shakers album, La Conferencia Secreta del Toto's Bar, which was in many ways their riposte to The Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Fatturosos moved to the USA, forming the jazz-fusion band Opa and touring with Airto Moreira (of Weather Report) before later moving to Brazil where they would play with such luminaries as Djavan and Milton Nascimento.

Their move to the USA mirrored that of many other musicians who fled when the military dictatorship arrived. The new regime championed the canto popular, a “back-to-basics” style of music, eschewing any electric instrumentation. For this reason (and others, of course) many of Uruguay's musical class joined the exodus. It would not be until the mid-1980s when rock music would return to the mainstream. Switch on the FM dial of your radio in Montevideo today and you'll see that songs from the period never really went away: 1980s stadium anthems and soft-rock ballads are standard fare, and are never celebrated more enthusiastically than on Uruguay's unique Nostalgia Night.

Now there are many popular rock bands in the country such as La Vela Perca, La Trampa or No Te Va Gustar, although arguably none has the originality of the “candombe beat” or the excitement of the Uruguayan Invasion bands. Celtic-influenced music is popular, and one of Montevideo's principal exponents is a lass from South Wales. But apart from the melodic pop of Jorge Drexler very little has been picked up on the international radar.

Time for another Uruguayan Invasion?